Black Market Mines Boom in Peru; An Un-Trashed Umbrella

And more about the human and environmental costs of renewable energy and digital technology—and how we can do better.

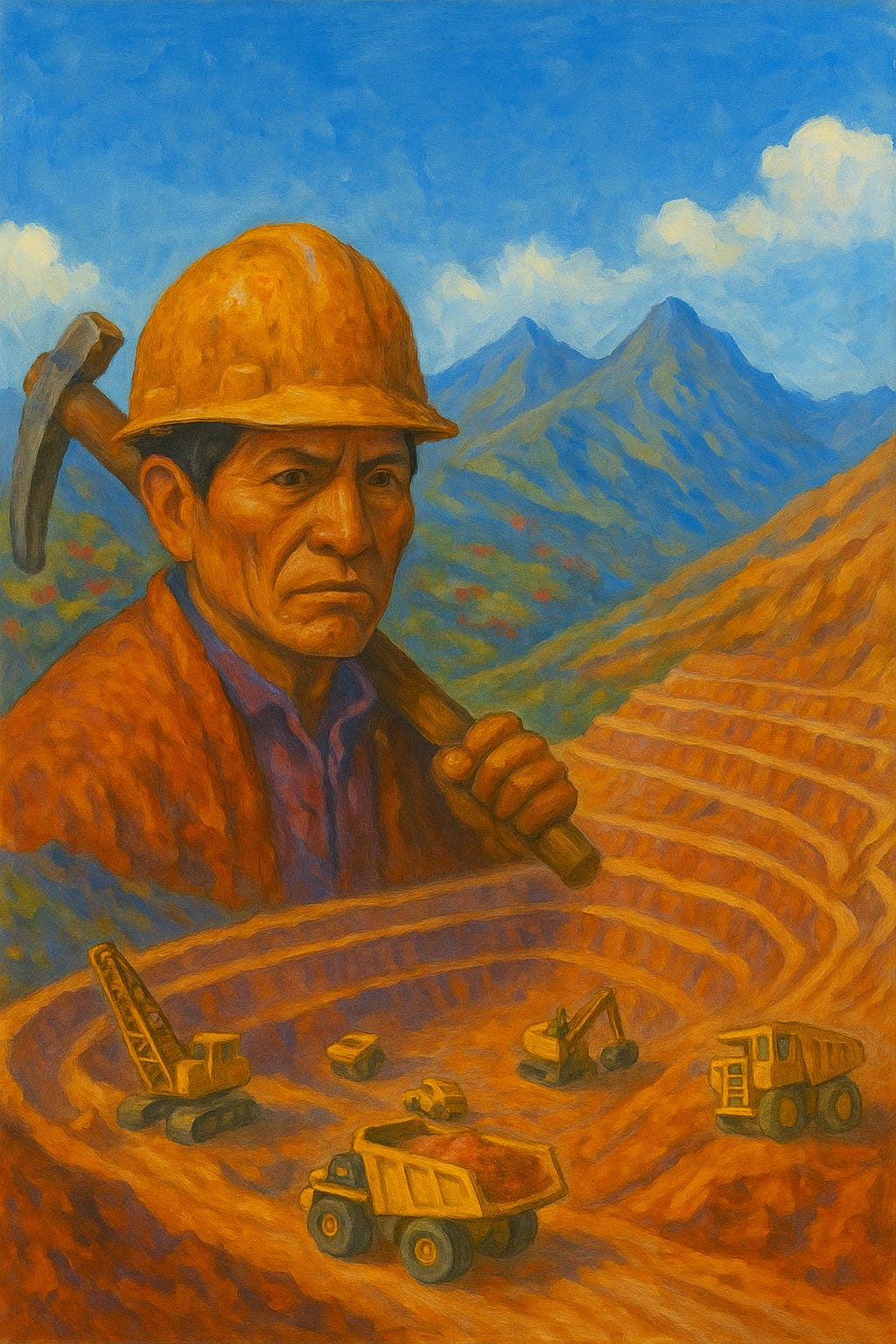

Black Market Mines Boom in Peru

High in the Peruvian Andes, an Indigenous community is battling against a multinational mining company—not because they want to prevent mining, but because they want to do it themselves.

“More than 13,000 feet above sea level, thousands of Quechua-speaking subsistence farmers have built what’s one of the largest informal copper mines in the world. The Apu Chunta quarry churns out about $300 million worth of the metal a year, funneling proceeds right back into the once impoverished community of Pamputa,” reports Bloomberg. (The Peruvian government this week confirmed that eye-opening figure.) “Pamputa’s once-sleepy village sustained by small crops and livestock is being completely revamped. Multistory brick buildings are rising. New roads, school buildings and a town square are under construction. Residents come and go in new $20,000-plus Toyota Hilux pickup trucks, and some have even bought expensive race horses.”

There’s just one hitch: that mine is illegal. Under Peruvian law, the community owns the land, where they have lived and farmed for centuries, but not what’s underneath it. Those mineral rights are held by MMG Ltd., a Chinese company which also owns two nearby, multi-billion dollar copper mines.

MMG wants to open a third one in Pamputa. The Peruvian government also wants this to happen. Peru is the world’s third biggest copper producer, and reaps scads of royalties from mining corporations. But illegal miners, like those at Pamputa, don’t pay anything.

MMG is piling on pressure. The company has filed more than 100 illegal mining complaints against the Pamputa miners. They’re also trying to get Apu Chunta removed from a government list of semi-tolerated “informal” mining operations. The Pamputa miners are fighting back in court, insisting the copper is theirs.

Artisanal mining is an extremely touchy issue in Peru, where about one-fifth of the population lives in poverty. Protests by artisanal miners shut down the country’s main highway last year. You can easily understand why the locals might feel they have more right to their own country’s mineral wealth than a foreign corporation. Nationwide, some 200,000 Peruvians are estimated to work as illegal miners, mostly going after gold and copper. There are so many of them that their trucks are crowding out those owned by big corporations on major mining roads. The business generates as much as $3 billion annually—more than the country’s drug trade.

But this isn’t a clear-cut story of virtuous Indigenous people standing up for their rights against mean multinational corporations. The small-scale mines sometimes use toxic chemicals, cut corners on safety measures and have been accused of employing children. It’s notable that the Pamputa miners wouldn’t let Bloomberg’s reporters see their operation. But it gets much worse: In some of Peru’s gold mines, artisanal miners have allegedly teamed up with criminal gangs to kidnap and murder dozens of company workers.

Peru isn’t the only place suffering. The worldwide hunger for copper is also driving a deadly epidemic of copper theft, something I examined in detail in Power Metal, the book. To quote myself: “In the past four years, the price of a ton of copper has shot from about $6,400 to more than $9,000. That, in turn, has made electrical wiring, equipment, and even raw metal fresh from the mines into juicy targets for thieves. All around the world, hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of the metal has been stolen—and countless lives have been lost.” The problem is probably at its most acute in South Africa: “In most places, power companies are a pretty dull business. But in South Africa they are under a literal assault, targeted by heavily armed gangs that have crippled the nation’s energy infrastructure and claimed an ever-growing number of lives. Practically every day, homes across the country are plunged into darkness, train lines shut down, water supplies cut off, and hospitals forced to close, all because thieves are targeting the material that carries electricity: copper.”

None of these troubles are likely to get better any time soon. A world run on renewable electricity and digital machinery is a world with a titanic need for copper. We won’t get all that we need without some conflict.

Sorry to interrupt, but: This newsletter is one of the ways I earn a living in these difficult times. If you find these dispatches interesting and/or useful, or if you just want to keep independent journalism alive in the Age of Oligarchs, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. A bargain at just $5 a month—less than a couple of tacos!

This Week in Un-Trashing

Clever re-use of an old umbrella—converted into a funnel to capture rainwater! Spotted on Valdes Island, Canada.

Book News

What do critical metals have to do with digital security? C’mon find out at my talk at MacDevOpsYVR, a programmer’s confab in Vancouver, on June 13.

More News Worth Knowing

📋 COP 30 Must Address Critical Metals

⛭ India to Open First E-waste Recycling Hub

☠️ Myanmar Rare Earth Mines Blamed for Toxins in Thai Rivers