Can America Build Better Batteries?

The US is finally investing in potentially cleaner, cheaper batteries. Plus: What's Critical? and Reader Writes

Greetings! Click on the video below to hear me read Building Better Batteries, or just scroll down to read it yourself.

Even as the United States pulls back from climate action on most fronts, American carmakers are starting to invest in an emerging technology that could have major upsides for electric vehicles and renewable energy: a better battery.

By now you’re probably unhappily familiar with some of the problems caused by the metals used in the batteries that currently power most electric vehicles and digital gadgets: the children working in Congolese cobalt mines, the rainforests bulldozed in Indonesia by the nickel industry, the desert ecosystem imperiled by lithium extraction in Chile. There are many ways to build batteries out of less troublesome materials, but lithium-cobalt-nickel batteries have been the world’s favorite for the last 20 years or so because nothing else matches their energy density—the amount of electricity packed into each gram of battery—and relatively low cost. But in recent years a major contender has emerged: batteries made with lithium, iron and phosphate, known as LFP batteries.

Iron and phosphate are much more readily available than cobalt and nickel, which makes LFP batteries significantly cheaper. They don’t have quite the energy density of their cobalt-nickel cousins, but years of industrial research have brought them very close—so close that a growing number of automakers are switching over to them. Worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency, “Lithium iron phosphate batteries now supply almost half the global electric car market up from less than 10% in 2020.” LFP batteries are also great for large-scale energy storage systems, like grid-scale batteries.

As usual, China is way out in front of the West in deploying this tech. (Even though LFP batteries were invented at the University of Texas.) As many as two-thirds of all new Chinese EVs use LFP batteries. And China dominates the entire supply chain for LFP batteries even more thoroughly than it does those of cobalt-nickel batteries, producing 98 percent of the refined chemicals required and a similar percentage of LFP battery cells.

But LFP battery making is finally taking off in North America. In May, Korean battery giant LG Energy Solution started producing LFP batteries at its factory in Michigan. (Not the one that ICE agents raided last week!) In July, the company also announced a planned joint venture with General Motors to produce LFP batteries in Tennessee. That same month, Tesla declared it has almost completed work on an LFP battery factory in Nevada. (The company currently uses LFP batteries it buys from China in many of its new vehicles, and also in all of its energy storage systems.) Meanwhile, Ford is building a $3 billion LFP battery complex in Michigan, where it expects to begin production next year.

I’m a full-time independent journalist, and this newsletter is one way I make my living. If you find it useful or interesting, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. Just $5 a month! Can’t afford it? No problem. You can still help by clicking the Like or Restack buttons at the bottom of this email. In any case, thanks for reading.

Big though these facilities will be, they’re just initial steps in building a complete LFP supply chain outside of China. Ford’s plant will use technology licensed from Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., China’s top battery maker. And all the American factories will rely on China for their key ingredient, the processed lithium-iron-phosphate powder from which the batteries’ cathodes are made. The US has plenty of raw iron and phosphates, but lacks the capacity to process them into cathode material. A handful of US and Canadian startups are trying to break China’s monopoly with their own processes for making cathode materials.

LFP batteries have other shortcomings. They don’t perform as well in cold temperatures as nickel-cobalt batteries do. They still require lithium, much of which comes from that imperiled Chilean desert. And as I explained in Power Metal, the book, “Most of the world’s phosphate rock is in Morocco and the Western Sahara, where a separatist movement has long simmered. Florida is another significant source, but the Center for Biological Diversity warns that phosphate mines there ‘displace plants and animals and eat up thousands of acres of valuable habitat that are impossible to restore to their natural state.’”

And of course, the Trump administration’s tariffs on imported materials and rollback of support for electric vehicles further complicates things.

All that said, the growing importance of LFP batteries seems on balance like a positive development. They have the potential to significantly lower the costs of electric cars, which will encourage more people to buy them, and of grid-scale electricity storage, which we need to make solar and wind power genuinely feasible replacements for fossil fuels. Plus, we won’t need as much nickel and cobalt.

What’s more, LFPs aren’t the only promising potential alternatives to nickel-cobalt batteries. A whole range of others are in development, including sodium-ion batteries, solid-state and silicon carbon batteries. Like every other aspect of the energy transition, there is no single solution that will take us to a carbon-free future. But the more pathways we can find, the better chance we have of getting there.

What’s Critical? Tell the Government!

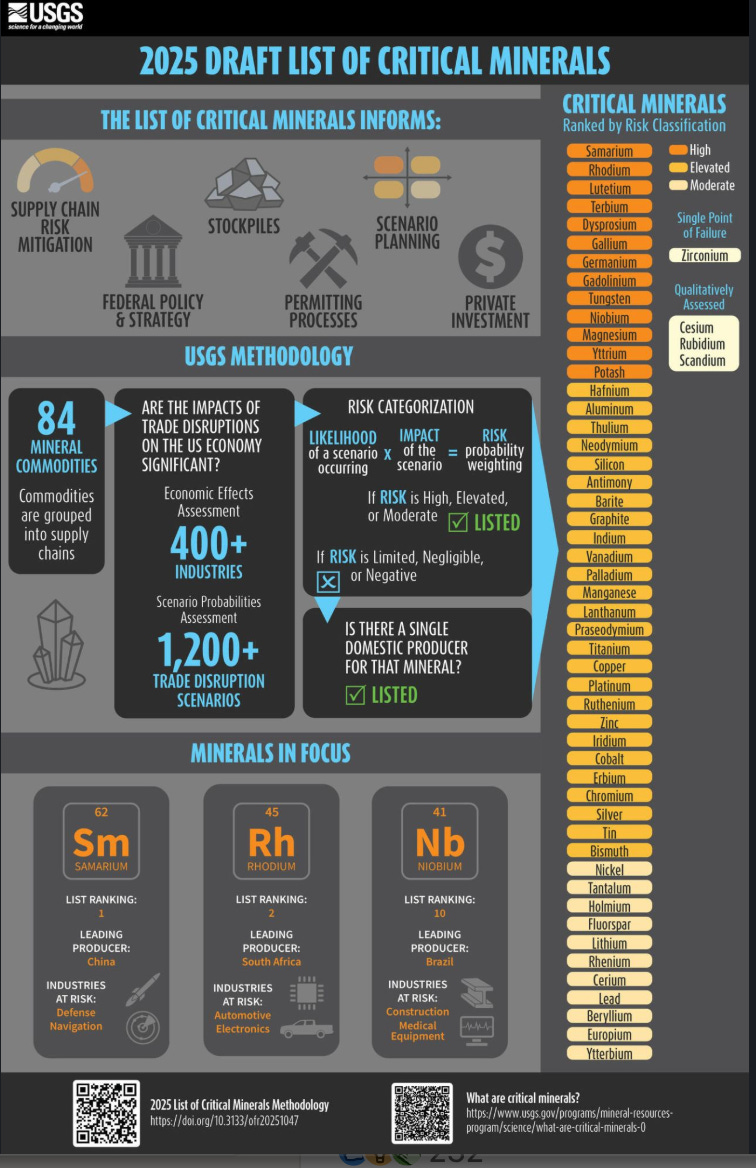

The US has published a draft list of what it considers critical minerals, by which it means minerals that are very important to the nation’s economy or defense, but which come via risky supply chains. The final list will be used to guide federal investment and permitting decisions as well as possible policies like tax incentives. In other words, it’s important. You can see the draft list below. If you’ve got anything to say about it, public comment is open until September 25.

Reader Writes

Julie Lucas, a mining industry veteran and sustainability advocate, offers this important context to last week’s article about how American mining companies are letting billions of dollars worth of critical metals go to waste:

Mining companies have a (hopefully obvious) incentive to pull as many metals as they can from every ton of ore they extract from the ground, but there are often technological challenges that aren’t necessarily apparent to folks outside the industry. Metallurgy is a science, but it also can feel like an art as you try to determine the best way to liberate a metal from the mineral it's tied up within. On the Iron Range in Minnesota, we used to mine hematite until the 1960s and now we mine magnetite. Both iron, but only one is magnetic and able to be separated from the remaining rock by massive electromagnets. To pull any hematite from the ore would require an entirely separate process that may simply not make economic sense for our facilities here. Accessing more metals from every ton is critical, but I don't think it's the slam dunk some folks are portraying it to be.

More News Worth Knowing

🪓 “Trump wants mining. Federal mine safety workers are on the chopping block.”

🛡️ Trump drops tariffs on gold, uranium and tungsten. What’s tungsten and why is it so important? We need it for armor-piercing shells, among other things—and China makes almost all of it.

🚚 A 200 mile road might get cut through Alaskan wilderness to access copper.

♼ India’s dangerous e-waste recycling industry

🦌 “Sweden’s plans to mine rare-earth minerals could ruin the lives of Indigenous Sami reindeer herders”

🔋 Record-breaking energy storage project built with used EV batteries

Thanks! I'm a geologist and find this stuff fascinating. Indeed, only Morocco and W Sahara have significant P reserves, together with Florida. Phosphate is of course also an essential nutrient (together with Nitrogen and Potassium. Years ago I worked with a geologist who worked in different African countries to help them unlock smaller Potash reserves - I seem to remember Ugranda, Tanzania and Botswana (but I'd have to look that up).