Does Ukraine Have What Trump Wants?; High Cost of Free Parking

And more about the human and environmental costs of renewable energy and digital technology — and how we can do better.

Does Ukraine Have the Metals Trump Wants?

Click the arrow to hear this article:

Just days before President Trump called Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy a “dictator” who was somehow to blame for Russia’s invasion of his country, Trump floated the only slightly less controversial idea that Kyiv should pay the US for protection, in the form of Ukrainian minerals. “I told them I want the equivalent of like, $500 billion worth of rare earth, and they’ve essentially agreed to do that,” he said on Fox News last week. “We have to get something.”

Besides the glaring moral questions this proposal raises, there’s a practical one: Can Ukraine actually deliver what Trump wants?

First, I’m sure Trump is not talking only about rare earths. This is a term that confuses many people; it’s often mistakenly applied to all the critical metals we need for the Electro-Digital Age. In fact, rare earths are a subset of those critical metals. Rare earths are a group of 17 obscure, esoterically-named elements, like praseodymium and yttrium, that are crucial for electric car motors, cell phones, wind turbines, and a range of health and military technologies. The more familiar-sounding critical metals, like lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper, are not rare earths.

Anyway: Ukraine does have some rare earths. But no one knows exactly how much, or even where they are. Ukraine’s claims about its mineral riches are based on Soviet-era exploration that was carried out decades ago. “Unfortunately, there is no modern assessment" of rare earth reserves in Ukraine, the former director general of the Ukrainian Geological Survey told S&P Global. And there aren’t any active rare earth mines, either.

OK. But we do know that Ukraine holds sizable deposits of several other important metals and minerals, including:

Lithium, graphite, and to a lesser extent nickel and cobalt, all of which are needed for the batteries that run EVs, cell phones and other cordless electronics.

Titanium, important for many military technologies.

Gallium and germanium, essential for semiconductors, TV and phone screens, solar panels, and military gear.

In theory, gaining access to Ukraine’s minerals could not only make America money but help it reduce its dependence on China for these substances. The danger of that dependence was highlighted in December when Beijing banned exports of gallium and germanium. Breaking China’s critical metal dominance “is one of the main geopolitical drivers in Washington right now,” Bryan Bille, a policy expert at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, tells me.

And Ukraine is willing to cut some kind of deal. Kyiv has been courting American investment since 2023. According to The New York Times, that push included a Trump-Zelensky meeting, and visits to the US from Ukrainian officials pitching deals for lithium and titanium. As of earlier this week, the US and Ukraine are at least discussing some kind of metals-for-security deal.

Whatever happens at the abstract heights of international diplomacy, however, there are major obstacles on the ground. Ukraine’s metals aren’t piled up in a treasure chamber somewhere. They’re in the ground—often in ground that Russian troops are standing on.

As much as half of Ukraine’s total mineral resources are estimated to be in the four eastern regions largely occupied by Russia. At least two established lithium deposits are in Russian-held territory, and another is just a few miles from the current front line. Few investors want to put their cash into mines within artillery range of a war zone.

Mines also require lots of energy, and the war has mauled Ukraine’s power grid. Ditto for roads and other transportation infrastructure. Plus there’s the inevitable environmental damage to be considered. Critical metal mining in Ukraine “has the potential to impact wetlands and rivers, old-growth forest and steppe,” cautions the Conflict and Environment Observatory.

“Given these barriers to mining and investment, we don't expect any new substantial critical mineral supply anytime soon,” says Bille. Nor, it seems, should Ukraine expect to get any new substantial help from America anytime soon.

“The High Cost of Free Parking”—A Requiem

One of the most infuriating of the many ways we subsidize the automobile industry is through free parking. As I wrote in Power Metal, the book: “Cars mostly occupy public space. They are parked by the millions on public streets. There is usually no charge for this enormous gift of real estate we collectively bestow on cars….Across the United States, there are as many as two billion parking spaces— seven for each motor vehicle.”

No one did more to raise awareness about this hopelessly unsexy but hugely important issue than urban planner and UCLA professor emeritus Donald Shoup, aka “Shoup Dogg.” Sadly, he died earlier this month. His writings, especially The High Cost of Free Parking, and his activism have played a huge role in getting cities to finally start rethinking how we’ve allowed cars to take over streets. May his name be for a blessing.

Barely Relevant But Cool Anyway

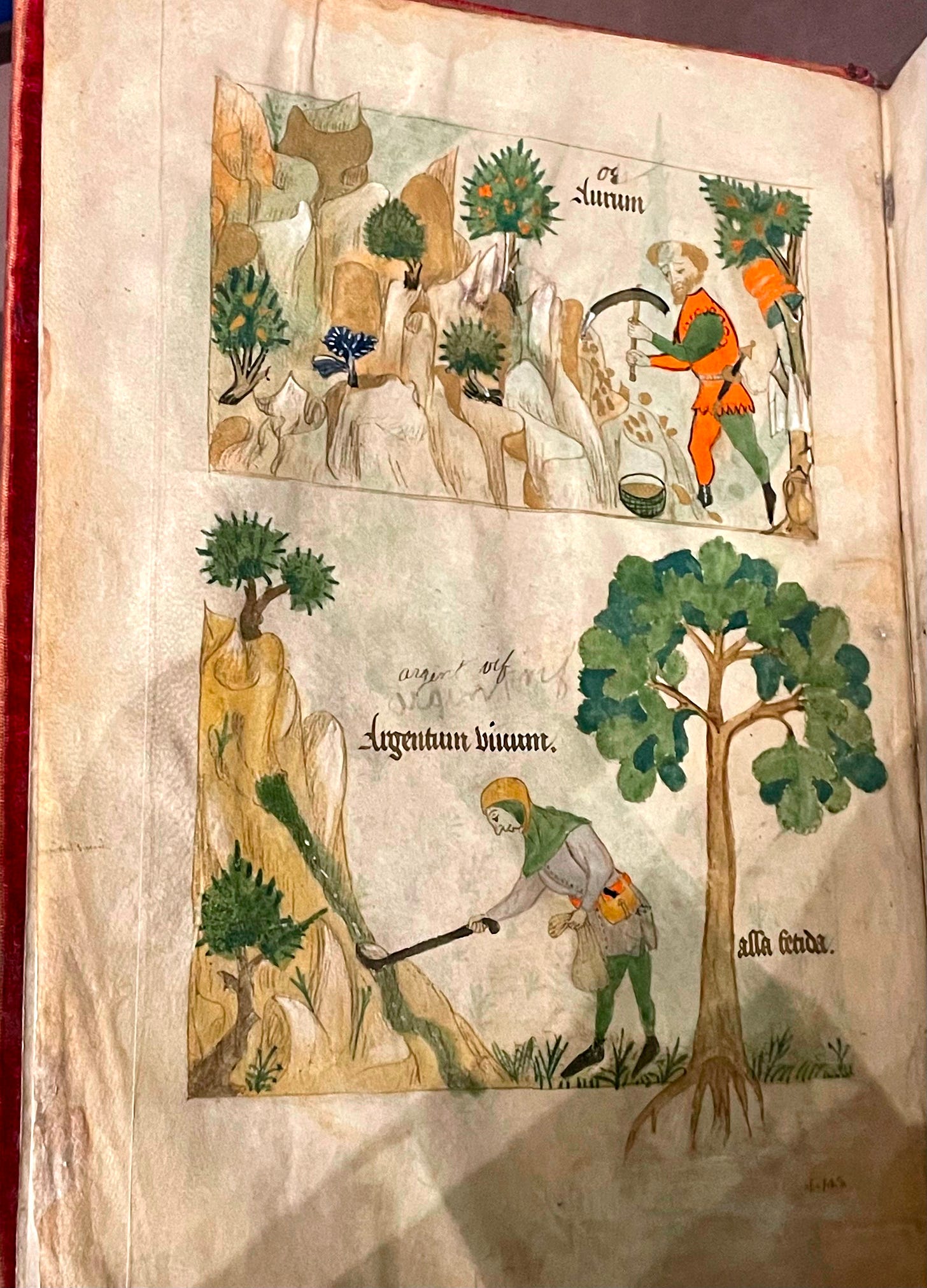

A couple of weeks ago I visited New York’s Morgan Library, a place I’d somehow never heard of before, which turns out to be a dazzling palace in the middle of Manhattan stuffed with historical books and manuscripts. This fanciful 14th century depiction of gold and mercury miners snagged my eye.

More News Worth Knowing

🔋 Chinese Scientists Claim They’ve Massively Extended Battery Life

🏹 Uncontacted Hunter-Gatherers Endangered by Nickel Mining

🪦 The Stolen Grave Markers of Brooklyn (hat tip to Jennifer Turner at @wilsonCEF!)

Timely and helpful! Thanks, Vince!

Now I wonder whether this information got to His Majesty after his initial remark about making a deal and led to his abandonment of Ukraine. (Smart Russians would have made sure it did reach him.) He may now be assuming he can get a good deal from his buddy Putin by leaving the mineral-rich areas under Russian occupation.