How Sludge and Shrimp Shells Could Power Your EV; Of Trade Wars and Sand; Brad Pitt Cameo!

And more about the human and environmental costs of renewable energy and digital technology—and how we can do better.

Many thanks to the many of you who have upgraded to a paid subscription in the last few weeks! If you’re not one of them, I hope you’ll consider it.

I’ve always been an independent journalist, mostly making my living as a magazine freelancer. But that industry is dying. I still believe independent journalism can make a difference in the world, and I intend to keep it up. But to do that, I could really use your help. If you find this newsletter interesting and the issues I cover important, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. It costs just $5 a month for a basic sub—less than a single happy hour beer, and no tip required! Even better: If you sign up as a Founding Member, I’ll send you a signed copy of Power Metal, the book!

Don’t want to pay right now? No problem. You can still help by clicking the Like or Restack buttons at the bottom of this email, forwarding this newsletter to friends, or sharing it on your favorite socials. In any case, thanks for reading!

How Sludge and Shrimp Shells Could Power Your EV

While I was at the University of Missouri last week for a book talk, I was lucky enough to visit a lab where researchers are working on an ingenious way to harvest rare earths from an all-American source that doesn’t require digging giant holes in the ground. The source: toxic mine waste. The tool: crushed-up crustaceans.

Missouri was once a major lead and iron mining state, and the industry left behind the usual trash—mountains of waste rock and pools of toxic runoff. Some of that gunk, though, contains critical metals, including rare earths. No one cared about those obscure elements back when the mines were big business, but today, they are not only valuable but of increasing geopolitical importance as the US-China trade war grinds on.

With that in mind, John Earwood, a grad student at the university’s engineering school working with professor Baolin Deng, has figured out a technique to pull out neodymium—a rare earth element used to make electric vehicle motors, among other things—from some of that waste.

You start with a powdered substance called chitosan, a biopolymer similar to cellulose that is made mainly from ground-up shrimp and crustacean shells. Next, dissolve it in an alkaline solution to turn it into a kind of sponge-like gel. Then embed neodymium particles into the gel, and use chemicals to pull them back out again. Very roughly speaking, that leaves neodymium-shaped holes in the gel’s chemical structure. Next, place discs of the gel into liquid waste from an old iron mine. Neodymium in the waste slides into those holes. “It’s like a puzzle piece clicking into place,” says Earwood. Once the gel has soaked up plenty of metal, you pull it out and treat it with chemicals to extract pure neodymium.

Cool science, right? Also, potentially very useful. There are vast quantities of critical metals hidden in the hundreds of billions of tons of mining waste all over the world—elements that weren’t in demand when the original mine was operating, or that were too difficult to extract with the technology of the time. But we want them now, and here they are conveniently already above ground. The dirty, difficult, energy-intensive work of digging them up has already been done. So that mining waste could be a relatively clean, efficient source of critical metals if we can just figure out effective techniques to extract them.

Earwood is far from the only researcher who realizes this. There are many other projects underway in many places with similar goals. Researchers in West Virginia are working on extracting rare earths from coal mine runoff. Mining giant Freeport-McMoran is trying to pull copper out of waste rock at one of its Arizona mines. Another mining colossus, Rio Tinto, is backing Regeneration, a startup aimed at recovering metals from mine waste. The list goes on.

So far, however, none of these efforts have hit the market in a big way. As far as I know, they’re pretty much all in the startup or research phase, with many showing promise but none yet proven to be commercially viable at scale.

That goes for Earwood’s system, too. While his gel is good at grabbing neodymium, it’s not perfect; it also grabs other, unwanted elements, limiting its effectiveness. Plus, though the main ingredient, chitosan, is safe and sustainable, some of the chemicals involved are toxic. “It looks really good in the lab,” says Earwood. “But there’s always the question of, ‘How do you get it to work at commercial scale?’”

Still, there are plenty of grounds to be optimistic about the overall concept of getting metals from mine waste . The metals are there, the demand is there, and the technologies to bridge the gap exist. Who knows? Some day soon your EV’s motor might be made from rare earths rescued from Missouri mine sludge. And you’ll have shrimp to thank.

Vietnam’s Booming Economy is Built on Cambodian Sand

(Why a post about sand, of all things? Here’s why.) President Trump’s first trade war with China pushed many companies to relocate to Vietnam, spurring a breakneck expansion of factories there. To service all those new factories, the Vietnamese government has launched a massive road-building campaign. But building those roads requires millions of tons of sand, and Vietnam doesn’t want to dredge that sand from its own rivers, with all the environmental damage that would entail. Instead, it is importing the grains from Cambodia. Using satellite imagery, Bloomberg has put together an eye-opening investigation showing exactly how hundreds of boats are sucking up sand from the bottom of the Mekong and carrying it across the border to Vietnam. Cambodia’s sand exports have grown almost a hundred-fold since 2021—but at the cost of collapsing river banks, which take down people’s homes with them.

Power Metal Book News

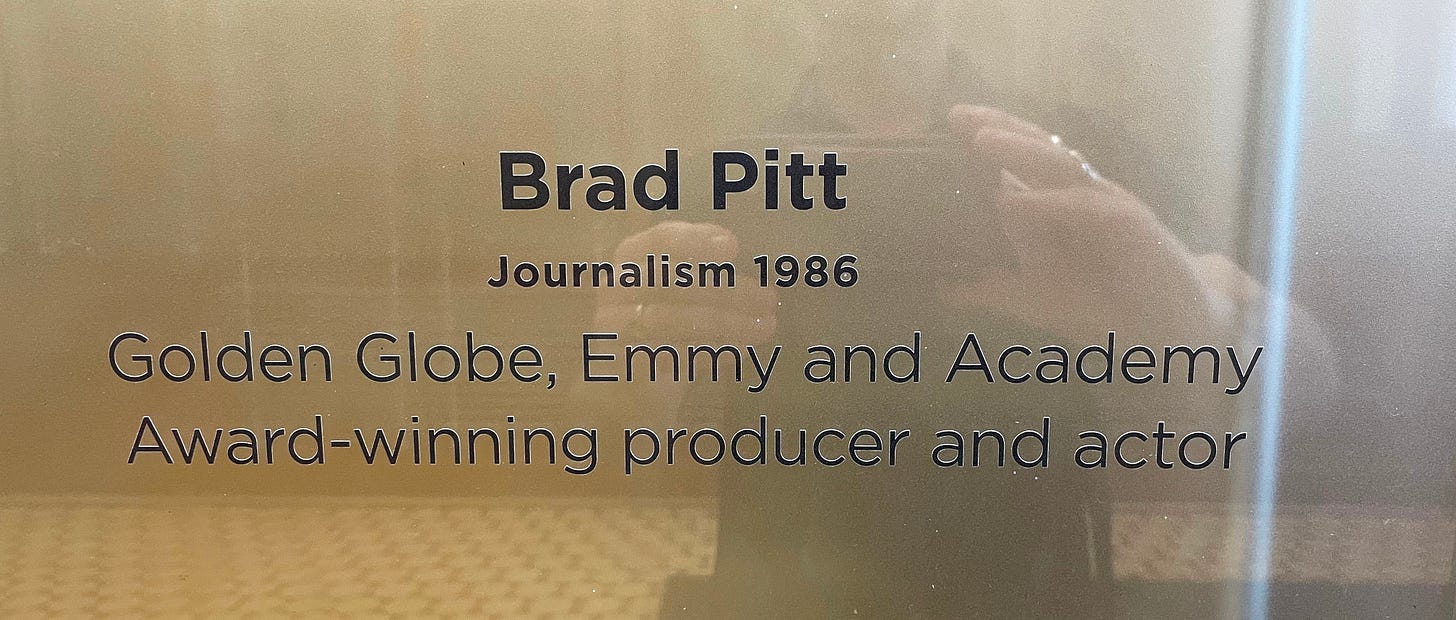

Many thanks to the inimitable Sara Shipley Hiles for hosting me last week at the University of Missouri. Who knew their Columbia campus was so gorgeous?

Also: who knew this guy studied journalism there?!

Meanwhile, thanks to Foreign Affairs magazine for this review of Power Metal and also The War Below, another fine book on critical metals. The Columbian newspaper also recommends them both.

I’ll be talking about Power Metal, the book, with The North Shore Writers Association in Vancouver on April 28, and at Seattle’s Town Hall on May 5. Both open to the public. Come on down!

More News Worth Knowing

🤔 How Much Rare Earth Leverage Does China Really Have? Less than you might think, this piece argues. Elon Musk, however, is worried!

⏩ Trump To Fast-Track New US Mines

🔴 Republican States Rely Most on Renewables

✝️ In Indiana, Installing Solar Panels is a Holy Calling

“Once the gel has soaked up plenty of metal, you pull it out and treat it with chemicals to extract pure neodymium” And this on an industrial scale, so I guess we swap one set of toxic chemicals for another, and this will be kinder to the Planet, I don’t think so, anyways the Planet doesn’t care, but the people might 👉 “After Skool - George Carlin - The Planet Isn't Going Anywhere. WE ARE!” https://youtu.be/09FmRNb3Krg?si=u59RVG5qHWM8dGGo 🤔